Story : Baba will come today : Anisul Hoque

Translated from the Bengali into English by Mohammad Shafiqul Islam

Baba will come today. It’s long I didn’t see him. Whenever I remember Baba, the smell of himkobori coconut oil hits my nose—in his hair he uses himkobori oil that has a strong smell. Before going out for a bath, Baba must rub coconut oil in the hair. Reddish in colour, the oil thickens like a soap in winter. He then struggles to get the oil out—oil doesn’t come out even if the uncapped bottle is repeatedly jerked. There are two ways to liquefy the oil: the bottle may be put in the sun, but it takes time, and Baba can’t wait so long. And the other option is to put the bottle by the fireplace, but it’s hazardous too—earlier a bottle burst. So Baba has found a new way to liquefy coagulated oil. With a jute-chalk, if he can take out a little from the bottle, he rubs it on the hair.

From his habit of using coconut oil in his hair this way, one can anticipate his head is full of dense black hair, but it’s not real—he’s almost bald-headed. To protect some hair that his head is covered with, Baba probably uses this himkobori oil with such care.

Last night as soon as I woke up, the smell of the coconut oil smacked my nose. I couldn’t figure out where I was then. It seemed I was sleeping at our home in Rajshahi. In the cot designed with conifer, just like a small roller. Those things spin too—I’d turned those small pieces of wood around, twisting thread in the fingers. In darkness, it seemed Maya was lying beside me. In trouble with worms, she gnashed her teeth the whole night. In a frame on the wall on the left side was certainly hanging my embroidery set—“That flowers bloom and fall is the rule of nature . . .” I was still slumbering, everything appeared in disarray, so it was taking time to figure out the time and place. Then slowly did I come back to reality—now I’m lying on a bed in the Women’s Rehabilitation Centre in Dhanmondi. In a bit away, Chobi was lying on another bed, Saima beside her. The whole world seems to lament on if one wakes up at midnight. The light from the verandah came to the room through the opening of the glass window over the blue curtain. Good that memories of those unbearable days didn’t resurface. Sometimes in sleep it seems I’m inside a dark cave, pitch dark, terrible, beastly—oh, who’s putting such a heavy boulder on the chest?

Since morning, I’m very excited as Baba is coming today. Taking shower earlier and wearing a clean sari, I’m now waiting with all excitement, strolling from this door to that. I’ve also finished my meal; besides, I’m not feeling hungry at all. Now I’m waiting in the rearmost verandah, my eyes on some clothes stirring in breeze. Saima has taken a bath late today too, drops of water still falling from her wet clothes on the floor. The water has changed the direction of the ants moving in rows under the clothes. How strange the world is! Deliberately or not, if people put their footsteps or drop some water, tiny beings are bound to change their directions, but the people don’t notice that. Some powerful people also make many common people’s lives difficult. Every life has its individual stories, every person has different histories of growing up since birth, their everyday life with parents, siblings, neighbours, and relatives, and in every person’s mind-sky holds a vast world. Like ants, human lives also get messed up in war, conflicts, and man-made or natural calamities.

Lots of trees are around this Dhanmondi house. If one stands on the verandah, they have a distinct smell from the trees. It’s now probably spring. The month of Chaitra? The mango trees have lots of buds and flowers—how fragrant! And see under the trees, the soil is covered with mango flowers. In our Rajshahi house, there are many mango trees too; one can collect mangoes from the roof. And in the mango season, I was almost addicted to picking up mangoes. In Rajshahi, there’s a rule—no one should pick mangoes from others’ trees, but if they are fallen under the trees, anyone can pick them up. Every night Baba and I went out with a torchlight in hand, wandered under mango trees, and my sari anchal became full with mangoes. And when dawn broke, we all were under the trees again. What a longing!

During summer last year we couldn’t pick up mangoes. This year it’s just the time of buds; probably we can go this time. Can we really go? Who knows? Shall I ever get back my yesterdays.

I’ll certainly do. Baba is coming, so I’ll go to Rajshahi with him—that very house of ours at Pakurtola. Stepping on the yard, I’ll put off sandals and storm to the draw-well. It’s long I bathed with cold water and heard cacophonies of bamboos with which buckets are tied to draw water from the well.

What will Ma do seeing me? Will she start weeping, embracing me? I have to buy shahzadi zorda for her. Now I’m recalling my mother’s face—vermilion on the forehead, bangles in hands, the fair and humble face, our all-enduring mother. Betel-leaves inside her mouth, black teeth, and red lips. And my younger sister Maya. How old is she now? Or she’s still the same as I saw her? How older can one become in only one year?

Dada has admitted into Medical College again as I’ve come to know. Good that Baba’s dream will come true. As noncooperation movement kicked off, Dada took part in it and began to scrape exams at college—Baba was indeed worried. Would his dream to make his son a doctor turn into ashes? No, it wouldn’t. Everyone would find their own ways. Now the country is independent. Now Dada serves people of an independent country. Everything would be running well. I have to begin anew again too, forgetting all the torments, terror, depression, dishonour, and afflictions of the previous year.

One year ago it was such a noontime in spring. Sitting on the mango branch on the south, when a cuckoo began to call out in a melancholic tune, I quickly went away to our bookshelf and opened the book Putul Nacher Itikotha that Shyamal da gifted me. On the first page of the book was only a word ‘YOU’ that Shyamal da wrote with his own hand. The cuckoo calling out tunefully took me away to the book. It must have been on 27 March. No vehicles were found on the streets. We all went out with only a few necessary things. The Chaitra sun was unbearably scorching. In my hand was a bag of clothes and Shyamal da’s book . . . and the cuckoo was still calling out . . . it couldn’t figure out anything else . . . this uncertainty, fear, curfew, mysterious people wandering around our house, their shadows . . . we couldn’t go far, within moments a jeep halted before us. Baba said it was Chairman sahib’s. . . . Master, where’re you going? Let me lift you . . . Chairman got down along with a few other people who came forward to me and pulled me up on the car forcibly . . . fortunately Maya was younger, or they don’t make a difference between the young and old? . . . But now we know they didn’t take Maya . . . Baba was crying out, Leave Asha, take rather me—where do you want to take us? We’ll take you too, Master . . . I was inside the jeep, trembling like a chick clutched by a vulture. I couldn’t know what happened to Baba and Ma.

Then I was taken to an army officer in the local Thana; three more girls were weeping in the house . . . When Chairman came, I held his leg and said—Kakababu, your daughter Sultana is my friend; I’ve played a lot with her. Please save me. He left jerking me off. Then army jeep, two military sepoys sitting close by . . . I jumped off the running jeep . . . didn’t know anything else . . . became senseless . . . as soon as I came to my senses, I discovered myself on the hospital bed, bandage on the head. After three days or so, no matter I got back to health or not, the first man who assaulted me was a Bengali . . . that night several men violated me one after another. No, I don’t want to recall those traumatic memories—from bunker to bunker, beastly life, wearing only a dirty blouse and a petticoat, because I may commit suicide if sari is provided. Many girls were in the same room; Nasrin apa, studying in the last year at Rajshahi University—ah, how beautiful she was—told me Asha, keep alive, that’s important; we shall certainly earn the victory. Our body condition was vulnerable, so was our head’s—this way nine months passed. So many deaths, so much blood, beastliness, and then once when Indian soldiers entered the bunker with the news of independence, we were so emotional and frightened once again that we turned unconscious . . .

First I was taken to a hospital; when I came to my senses, the first thing I did was that I said I’d go to Baba, but when I was asked my father’s name, I couldn’t recall his name—I was only crying and shedding tears. So the benefit was that I was lifted to a helicopter, was directly brought to Dhaka. After one month in the hospital, I’m now staying in the Women’s Rehabilitation Centre, Dhanmondi.

In the beginning, I didn’t want to communicate with anyone from my family, but as time went by and my health was improving—in the meantime I had an abortion—I began to feel mentally well and recollect memories. I was deeply feeling to share my sorrows and sufferings with my family members—Baba, Ma, Dada, Shyamol, Maya—and tried to communicate with them. I gave my home address to the director of the centre and she wrote a letter to them. I was so excited that I was counting days for Baba’s arrival. I knew he’d storm to the centre after receiving the letter. I couldn’t keep my eyes away from the road; my urge was unbound to see Baba’s face; I was waiting for the himkobori coconut oil to hit my nose . . . .

No, Baba didn’t come; instead a letter arrived. The home was devastated in the war, so he was busy repairing, and Dada was busy with study in the Medical College.

I read the letter and weep; the tears fall on the letter and ink spreads to smudge the words. Instantly I began to write a letter—Baba, please come at least for once, I’m deeply feeling to see you.

Baba wrote back he’d come on 22 March.

Today is the day.

I took leave from the director apa yesterday, “Apa, you’ve done a lot for me; I’ll never forget you.” Keeping her hand on my head, she said, “Good luck for you! Stay well and happy at home . . .”

A few moments ago Kulsum, the maid, came over, “Didi, will you leave today?”

“Yes, Kulsum, Baba will come today.”

“It’s already late; you can stay tonight and leave tomorrow.”

“Let Baba decide . . .”

Sitting nearby, Kulsum begins to weep, “Didi, you’ve home, but we’ve nowhere to go. Where should we go, what shall we eat, nowhere, nothing. We have to stay here . . . everyone will leave one by one; we’ll be alone here. If the centre closes, we’ll lose the job and have to beg alms.”

Kulsum, who is from the Dhangor community, is also an oppressed woman. After the war, she found no trace of her homestead, so she came back to the centre and the director gave her this job.

Why isn’t Baba coming? I walk to the gate and find Sagir Mia, the guard, dozing off. Seeing me, he says, “He’ll come, Apa. Trains don’t maintain schedules, you know.”

Sagir Mia is right—train schedules are a factor. Or else Baba was supposed to come by the night train and arrive around 8 or 10 am. Even if he takes some rest in a hotel, will he be so late?

Or Baba won’t come at all?

I feel like weeping, I feel chocked as if a fish-bone is stuck on the throat—such is the pain, the unbearable agony. I storm into the bathroom, sprinkle water in the face, and closing the door, I cry out loud.

The guard informs, “Asha Di, your father has come.”

Baba . . . the smell of himkobori coconut oil, the mango orchard in the dark with torchlight in hand . . . a High School teacher . . . the dearest person in my life . . .

I run to the waiting room to see Baba sitting. Seeing me, he stands up. Baba’s appearance has got a massive change—his hair has turned grey, black mark under his eyes, as if he turned so old in just one year’s time. I stormed to him—Baba . . . I hug him, he also holds me, but Baba’s sandals seem so hard, and then he starts crying. His whole body is shaking, he cries out loud and wails. I’m also crying on his chest, his tears falling on my head, all over my body . . .

Slowly Baba gets back to normal. I offered him a chair to sit on. Wiping tears, I tell him, “Baba, how is Ma?”

“Good.”

“Maya?”

“Good.”

“Dada?”

“Good. With the blessings of the Almighty everyone is well, Ma.”

“Baba, we’ll return by the night train, right? I’ve arranged everything. Only you have to sign a document in the office. You’re receiving your daughter, so you have to sign just for that . . .”

“Ma Asha, I’m wondering if I should tell you this. But I’m not taking you this time. Maya is growing up, so she has to be married off. Besides, we couldn’t finish repairing our house completely—where will you live? Ma, you rather stay a few months more here. . .”

It’s whirling in my ears, all the spaces are trembling like a boat in the storm, I can’t hear anything else from my father. Once I think I tell him—Baba, before the repairing is complete, you can’t take me home, then where are you living . . . it’ll result in nothing . . .

Baba leaves away. On stiff feet, I get back to my room and sit on the bed. Chobi, Chaya, and all are keeping their eyes on me. Let them do. I’ll carry on and live my life. I don’t care. Suddenly it comes to my mind, I didn’t have the smell of himkobori coconut oil from Baba’s hair.

In just one year, so many changes have taken place, even the smell of Baba’s hair.

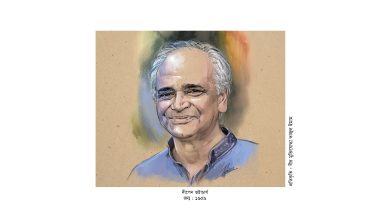

Anisul Hoque : Fictionist in Bangla Literature

Mohammad Shafiqul Islam—poet, translator, and academic—is Professor in the Department of English, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet

Illustration : Rajib Dotto