Series Novel : The Afternoon of the Seventh of March : Selina Hossain

Translated from Bangla by Mohammad Shafiqul Islam

Serial : 28

“At the Racecourse ground,” Kabir proudly declares, “Niazi will surrender today.”

Sabiha wipes her tears and emits, “I listened to Bangabandhu’s speech on the 7th of March at the Racecourse ground. Bangabandhu giving the historic speech raising the middle finger is still a fresh memory, but I can’t witness Niazi’s submission today.”

“Don’t be sad. Following the historic speech, we’ve indeed fought in the war and earned independence. Bangabandhu declared The struggle this time is a struggle for independence.”

Again Sabiha wipes her tears.

Matin stretches his hand towards Sabiha, and holding hers, he says, “We’ll take you all along with us. The war was indeed for us all.”

Sabiha nods right away, “Yes, it was for all of us, but we had more liabilities.”

Kabir and Matin say in unison, “You’ve been incarcerated in this room because of war. Your contributions will be one with the colours of our flag. Now let’s get on the jeep.”

Everyone comes out. Seeing them, the freedom fighters break down, some of whom wipe tears hiding behind them. Enduring extreme tortures and violence, they can see an independent country now, but they have to fight more in the future.

10

Sabiha accompanied by Nayan and Ashraf get back to her village. Descending from the boat, as she looks around, she can see and realize that the village stands still with marks of wounds caused by the war. The whole surrounding looks as if it were a watercolour painting, the village gaping empty amidst ruins of torched houses. No new colours have been added; various colours have formed in various ways. Somewhere ash colour dominates, somewhere the gloomy trees stand colourless, losing greens because of fire; grasses have been crashed beneath boots, and the soil has turned into the land of mass graves. As twenty to twenty-five or even fifty dead bodies have been buried together, the soil looks jagged. They can see lots of mass graves near and far. Drawing Ashraf’s attention, Sabiha asks, “Are my parents, brother, and sister alive, Ashraf?”

Ashraf remains silent. Nayan mutters softly, “All people in a war-stricken country are fated to look for their near and dear ones, immediately after the war. Your beloved Bishkhali river should also be asked How many dead bodies are you carrying, O Bishkhali? Have you taken them to the sea? Neither Ashraf nor I know anything of our families.”

“You’ll go home later, but I’m in my village now, Nayan.”

“Let’s look after them together. You’ll stay somewhere, we two will go out to find your family members. We’ll even go to your grandfather’s house, but don’t worry at all.”

“Where are you from, Majhi bhai,” Sabiha asks, taking a look at the boatman.

“Boloibunia, Ramna.”

“What’s the condition of the village?”

“Terrible. They’ve torched everything, killed lots of people. The razakars are worse.”

They listen to the boatman with rapt attention. At this point as soon as the boat is anchored in the ghat, Nayan gets down and walks forward. Ashraf helps Sabiha get down from the boat, holding her hand. “When will you return?” asks the boatman.

“Let’s see when we can.”

“I’ll wait for you.”

“No, you don’t need to wait. You can go if you find passengers.”

“Today you’re my guests. I salute you as freedom fighters.”

“Sabiha is from this village; she has also fought in the war.”

“Salute, Ma, thousands of salam to you!”

The boatman touches Sabiha’s feet. Immediately Ashraft pulls him up and tells him to go with them, “Let’s go to Sabiha’s house.”

“Ok, let’s go.”

The boatman walks in front of them, so Ashraf and Sabiha can walk hand in hand. Wounds in Ashraf’s hand have healed a bit—actually, the hand stretches until the elbow only. Holding his right hand, Sabiha is walking forward. Earlier when they met at Musa Camp, they only exchanged some glances for a few moments. Then she said with a smiling face, “I don’t have any sorrow.”

“Neither do I have. Whatever happened has been for independence, and we’ve earned our independence.”

While walking hand in hand, Ashraf and Sabiha can see lots of people of the village coming towards them. They neither shout slogans nor exhibit happiness in their faces; rather, they look coiled in profound sadness. Those who have come to them are no one of Sabiha’s family—she feels broken, wonders if her parents are still in the village. While leaving for war, I told my mother I’d come back freeing the country from enemies, but where’s Ma now? Sabiha thinks.

Getting close to her house, Sabiha can see everything has been devastated; she cries out loud. Ashraf can’t control her. She runs to the ashes and sits over there. Ashraf looks around and see everyone there is just watching. At this point, Wazed Miah comes forward.

“Here in this yard dead bodies of your parents and brother were lying.”

Taking a look at Wazed Miah, Sabiha tries to control herself.

“Uncle, you…”

“Ma, when the military people and the razakar Chairman went away, we buried them in the dark of the night. See, there, in that corner.”

Sabiha walks to the graves.

“Why three graves, Uncle?”

“The soldiers took your sister away.”

“O Allah, O Allah!”

Sabiha begins to weep again. Ashraf holds her and gets her seated on the ground, when she’s about to fall down. He says, “We met, and I’ll tell you about her later.”

“Only tell me if she’s alive.”

“No, she’s no more.”

“No? What do you say?”

Ashraf keeps silent. Wazed Miah puts his hand on Sabiha’s head, “Ma, where have you been so long?”

“I fought in the war, Uncle, participated in various operations and destroyed many of them, but failed in one—they caught me there.”

“I understand. I pray for you so you keep well. You all, now let’s go to my house. You need to eat something and take rest.”

“No, Uncle, I should go to Dhaka today.”

“What do you say, Ma? Your whole family has ruined.”

“I don’t think it’s that sort of ruin, Uncle, it’s a sacrifice for independence. I’ll come back again, will build a monument for martyrs here.”

“You’re right,” Ashraf responds immediately. “For this village, a martyred memorial should be built here; all of you should help build this.”

Everyone around shouts out, “In the name of Almighty, we’ll build a memorial in this house. Our liberation war, our memorial.”

Sadness for Sabiha and her family’s sacrifices now gets one with the glory of independence—everyone feels excited. Sabiha stops weeping too—it seems tears may stain the glorious achievement. Let tears turn into pleasures. She notices young boys and girls are running to them, flowers in their hands—schoolteachers too. They offer flowers to Ashraf and Sabiha and shout out, “You’re freedom fighters, our pride.”

Excitement continues to prevail for long. People of martyred families also turn up. Sabiha and Ashraf’s surroundings are adorned with flowers. The teachers say, “Salute to you! You’re the pride of our village, Sabiha.”

Sabiha has never thought she’d be given such a warm reception in the village. No one has asked about her pregnancy yet. Her eyes become teary, she wipes tears with her sari anchal.

“Don’t weep, Ma,” Wazed Miah consoles her.

“Uncle, I’m feeling broken, losing everything.”

Looking at everyone, Ashraf tells Sabiha, “You’ve lost your parents and siblings, that’s true, but all the people in the village stand by you, salute you—shouldn’t you feel very happy?”

She touches Wazed Miah’s feet to show respect.

“You’ve buried my parents; I’m grateful to you, Uncle. You didn’t leave the dead bodies for jackals. Engrossed in the thought of danger, you didn’t keep home—you’re a freedom fighter.”

“Didn’t Bangabandhu declare You have to face the enemies with whatever you have? We’ve indeed followed Bangabandhu’s words. We’ve faced the enemies courageously, even risking our lives. We all are heroic fighters.”

Hearing this, the boys and girls throw flowers above, also offering those to everyone standing close by. When they’re short of flowers, they give only petals.

“This is an exceptional scene,” Ashraf shouts in excitement. “Engraving this scene in the heart, we’ll go to Dhaka. Uncle, you all, pray for Sabiha. Little boys and girls, pray for your Sabiha Bubu so that she keeps well.”

“Sabiha Bubu will of course keep well.”

“I’ll come back again, my little brothers and sisters. Pluck flowers for me. If I get some from you, I’ll feel thankful to you. Say, we’re independent.”

“We’re independent, we’re free. We’re independent, we’re free.”

As Sabiha begins to walk to the river, the boys and girls follow her and slant slogans “We’re independent.” Ashraf offfers his love for them, putting hands on their heads. With bright eyes, they keep looking at them and say, “Freedom fighters, our brothers, please come to our village again.”

Nayan joins them and invites everyone, “Let’s sing together.”

“Which song?”

“My Bengal of gold, I love you. You haven’t learnt the song yet, so I’ll sing it standing before you, and then you’ll follow me. Okay?”

“Yes, we can.”

Nayan begins to sing. The gist of the song floats in the air. The grown-ups join the young, and all of them get to the riverbank, singing. Now Ashraf looks at Sabiha and murmurs, “Bishkhali, take us along with our song, be one with the Buriganga. Let the words of our independence flow through your currents.”

After a long time, Sabiha smiles and her face glows. She radiates, “This is a happy day for us.”

—-

Selina Hossain : Fictionist in Bangla Literature

Mohammad Shafiqul Islam : poet, translator and academic, teaches English as Associate Professor in the Department of English at Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet 3114, Bangladesh

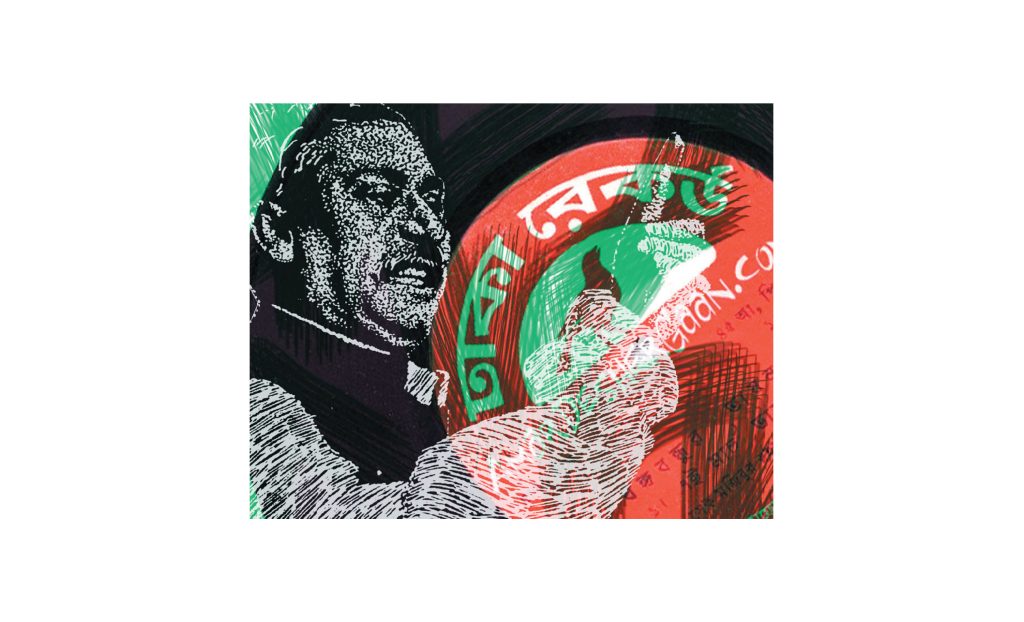

Illustration : Najib Tareque