Series Novel : The Afternoon of the Seventh of March : Selina Hossain

Translated from Bangla by Mohammad Shafiqul Islam

Serial : 27

Getting down from the launch, when everyone got on the raft, Ashraf lost his senses.

“You have to keep alive,” Badal told him, sobbing, “until we reach the camp.”

At last they reached the camp, and seeing him, Doctor Mahfuz said, “His hand is hanging with skin only; it must be amputated.”

“To be amputated?” Sahana began to cry. “Oh, Allah, my brother, what will happen to him?”

“Ah, Sahana, stop,” Badal softly yelled at her. “We’ll take you to the village, don’t worry.”

“No, I won’t go to village; I’ll go to my Bubu.” Just after a few moments, she said again, weeping, “I feel pain walking; all my body aches.”

Nayan got to another room with her.

Unable to bear extreme pain, Ashraf moaned too. As the doctor came over and gave him some medicine, bandaging the wounds, he felt a bit better.

Since then Ashraf has been waiting for recovery. In the meantime, another incident happens. It’s ten days since they came to the camp. The girl who used to look after Sahana storms to Ashraf, crying loudly.

“The girl whom you save from Pakistani army is no more; our attempts turned a failure. We didn’t inform you that she’d been senseless last two days.”

“Oh, what shall I tell Sabiha?”Ashraf puts his hand on the forehead, eyes teary. “How can I console her?”

“Don’t break down, Ashraf,” Nayan tries to convince him. “You have to get back to your health soon.”

“Try to arrange her proper burial.”

“I’ll see to that—you don’t need to worry at all.”

Ashraf closes his eyes, his body shivers, but he tries his best to control himself, although he can’t. Overtaking Sahana’s face, Sabiha’s surfaces before his eyes. Where’s Sabiha now—he thinks.

Now Sabiha is in a Pakistani camp—raising fingers, a Major is harshly asking her, “Bastard, tumhara naam kiya hyai—what’s your name?”

Sabiha remains silent, her anger gradually escalates, although her feature has broken down because of torture. “Bol, naam kiya—what’s your name?” Major shouts at her again.

“Joy to Bengal,” Sabiha shouts back.

Major gets furious and orders the soldiers, “Uchko torture cell me vej dou—throw her off to the torture cell.”

When she’s brought to the torture cell, an officer expresses his excitement, “Welcome! Sit down, please.”

A soldier has her sit on a chair, her feet trembling. Just catching up on the handle, she controls herself.

“Very nice girl! What’s your name?”

Still Sabiha shouts up, “Joy to Bengal.”

The officer bursts out in laughter and tells the soldier, “First, freshen her up, and then send her to my bedroom.”

As the soldier pulls her forward, she falls down on the floor, loses her senses. At this stage, he lands kick after kick on her, relentlessly badmouthing too. In a subconscious state of mind, she has carried an incident of another operation that she recalls now.

They launched an attack on a Pakistani camp. In front of the camp, there was a jeep—at that point, they were hiding behind bushes, waiting to attack. When the army officers were about to ride the jeep, Sabiha gave an order, “Fire,” she herself hurling a grenade at them. The jeep got burnt at constant firing and for hurling grenades. Those who were nearby fell down. With a hope of taking control of the camp, Sabiha’s team moved forward, firing, but some Pakistani soldiers shot them from behind. Bijoya received a bullet and fell down instantly. When others made an attempt to rescue Bijoya, Sabiha shouted at them, “No, don’t come forward. Go back to a safe place quickly—this is an order.”

All of them retreated, although they didn’t feel good doing this, but there was no alternative then—it’s not bravery to die like a coward. Keeping corpses of two others, along with Bojoya’s, they had to get back to the boat. In her subconscious mind, Ashraf appeared. It was a day in the beginning of the war. Seeing a bird fly close to the camp, Sabiha said, “O Bird, go tell him . . .” Where are you staying fighting Pakistani army now, Ashraf? The bird brought her news of Ashraf—she could hear it chirping , as if it were relaying Asharf’s words We’re prepared for the war, our interim government has been formed, oath-taking is done at Mujibnagar, Tajuddin Ahmad being Prime Minister. Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra has also kicked off. The whole country has been divided into eleven sectors. Don’t worry about me, Sabiha. Within a few days, guerrilla fighters will enter into the country; they’ll weaken the spirit and base of the Pakistani army, will present to the world the liberation war has started in Bangladesh. Joy to Bengal!

Still lying on the floor, Sabiha regains her senses and looks around. On another corner of the room, another girl is seated cross-legged. She comes to Sabiha. Sabiha murmurs, “You were there during the primary days of the war, Ashraf. Won’t you be there at the end of the war? Shall we meet again?”

It’s dark everywhere; there’s no one to respond.

The girl comes forward, “My name is Rashida. Razakars have brought me to this camp, but I want to flee from here. With a gun in his hand, a soldier is there outside. Will he shoot me if I try to flee?”

“Yes, he will.”

“Then shall I go?”

“No.”

“What should I do now?”

“Keep seated beside me.”

“If I stay here, they’ll . . .”

“During war, women’s bodies are tortured.”

Rashida begins to cry.

“Don’t cry. Always keep strong. Just imagine how you can smash them.”

“With an empty hand, how can I do that?”

“You have to act as per the situation, but keep mentally strong—don’t lose courage, don’t shed tears.”

“After independence of the country, what’ll happen in my life? My parents won’t welcome me home; everyone will hate me.”

Two soldiers thump the door open and drag the two girls from the floor toward another room, where four to five other girls have either been lying overturned or seated on the floor, some of whom moaning, some dead silent.

Shutting the door from outside, when the soldier goes away, Sabiha sits erect in front of the girls. Putting her two hands on the floor, she controls herself, Rashida sitting by her. Others also get up and sit in their own places, moaning stops, while one of them asks Sabiha, “Where have they caught you from?”

“From an operation that I led.”

“Have you participated in the war?”

“Yes, I have. I’ve also received training, can operate some arms too.”

“O Allah! Kudos to you, Apa! May you live long! We’re indeed helpless, couldn’t do anything.”

“This room is also a war field for us.”

“How? We’re captives to them.”

“They’ve swooped on us, assaulting our bodies, particularly our cunts. Our wombs will be shot again if we become pregnant.”

“Oh, dear Apa!”

“During war, women are tortured and violated this way, and for this, not we but the whole nation is responsible.”

“Apa, may Allah bless you!”

“In this camp, a girl bit a wicked soldier and pushed him down. Later, they shot her dead in an open field.”

“She’s our freedom fighter sister. Have you given her salutes?”

“We’ve done, but silently.”

“You’ve done it right, because times aren’t in our favour now. After the country’s independence, all the people will salute her, the government will bestow on her the state honour.”

“You’re right, well said.”

“No one of us have come to the military camp willingly; everyone has indeed participated in the war; everyone is fostering the dream of independence. We all are incarcerated in this hell just for independence; we’re fighting with all our strength and capacity—to wound the enemies biting is to fight in the war field too.”

“O, our Apa, dear Apa, may Allah give you a long life! May our parents understand the importance of war!” everyone bursts out crying.

“Don’t cry; it’s not time for shedding tears.”

“Will our parents take us back home?”

Sabiha becomes silent, doesn’t feel good talking anymore—indeed she’s feeling unwell, eventually falling flat on the floor. Before making love with her dream man, Ashraf, she’s abused by Pak soldiers—the thought induces her to remorse; she shuts her eyes off, while others lift her up on the cot. Neither sleep nor senselessness, but a sort of stupor steals her ability to think, pushing her into the deep sea of emptiness, as if she lost all the sap of her life; she’s now feeling choked. In this state of inebriation, it seems to her something has happened to Ashraf; probably he’s severely injured—his appearance comes into her view. Where are you, Ashraf? I’m looking forward to the war field. Grab me close, take me far away, crossing boundaries of life and death . . . . Amidst this state of limpness, she rises up and sits on the bed. Looking at the girls, she says, “I’ll drink some water.”

They keep silent, because there’s no water in the room; it’s locked from outside too. Upon their need, the soldiers open and close the door and provide food. And they take the girls to different rooms when required.

“We can’t give you water, Apa.”

“It’s ok. Next time I’ll arrange water in the room, talking to them.”

“We sought to them earlier, but they didn’t listen to us.”

“If they still refuse, I’ll kick them.”

“Apa, they’ll kill you.”

“Let them do, but before death . . .” Sabiha gets silent before finishing her words. Bangabandhu’s speech surfaces up If there’s any sinister move to annihilate the people of this country, the Bangalis, you’ll have to keep watch carefully. “Sisters, listen, we have to work a lot. Who among you have listened to Bangabandhu’s speech?”

“I have. Me too. Everyone responds in the positive—we’ve listened to the speech on the radio.”

“We didn’t have any radio at our home, so I listened to it in the market. I can recall a line Build a fortress in each and every house.”

Another girl says, “I can remember We’ll have them starve to death. We’ll make them go without water and let them die.”

“I remember What have we got?” I can’t remember the rest in full, but what I understood is We’ve bought arms to save our country, but those are used against the poor and helpless people of the country.”

“Wow, you’ve remembered many things, I can see.”

“Why not, we indeed listened to the speech with all attention, stamped his words into our brain. We’ve prepared ourselves for the war—to stay in this Pakistani camp is fighting in the war for us.”

“Bravo!” Sabiha shouts out the slogan “Joy to Bengal,” the other girls joining her—the surrounding gets reverberated with slogan after slogan. For the ear-piercing sound, the door opens, as four soldiers kicks the door—pulling the girls out one after another. Dilara doesn’t want to go, but a soldier forcibly takes her out, while the other yanks Sabiha. As she looks forward, she can see Nadira grappling with another soldier. At some point, he aims his gun barrel at her back.

“No,” Sabiha shouts out loud. Hearing this, the soldier looks back once and then shoots Nadira at the back, the bullet piercing her body—she falls down on the ground. The other soldier gets in another room with Sabiha and perpetrates tortures on her.

As Sabiha has to keep incarcerated five months or so, she doesn’t know anything about what happened outside. She can simply realize she’s pregnant—an embryo inside her womb; menses have stopped. Putting her hand on the baby bump, she speaks to herself, “This is also my war—for independence everyone has to sacrifice their bodies. If Ashraf lost his hands or legs, that’s for independence too—there’s no way to think anything more.” In pain and suffering for tortures, she moans, attempts to stand on her own feet, but her physical condition doesn’t support—at last she stands up.

One day, when they can hear freedom fighters shouting out the slogan in unison “Joy to Bengal,” Sabiha and everyone else prick up their ears to listen to it properly. Nur Jahan whispers in an exhausted voice, “Has the country become independent? Why then can we hear the slogan Joy to Bengal?”

They all get seated straight while slogans float up reverberating around. Each of the girls doesn’t feel pain in their bodies anymore, as if something healed their wounds, as if they regained all their strength. Suddenly someone says, “Yes, the country has become independent.”

The freedom fighters come to the camp but find none there. Kabir shouts out, “Sons of bitches have fled away.”

“Now it’s clear—I’ve seen a jeep leaving this place.”

“They could assume their days were getting numbered.”

“That’s why they were ready to flee and so did they to save themselves. Or else we’d destroy them all.”

Swiftly they pay extra attention. Matin says, “Women are crying out somewhere.”

Fatema cries out, “We’re locked up here, please open the door.”

The freedom fighters chant the slogan Joy to Bengal.

Hearing their cry, the freedom fighters move forward and see a room locked from outside. With the rifle butt, they break the lock and open the door. They shout together, “We’ve shed blood, we’ve earned independence.”

Selina Hossain : Fictionist in Bangla Literature

Mohammad Shafiqul Islam : poet, translator and academic, teaches English as Associate Professor in the Department of English at Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet 3114, Bangladesh

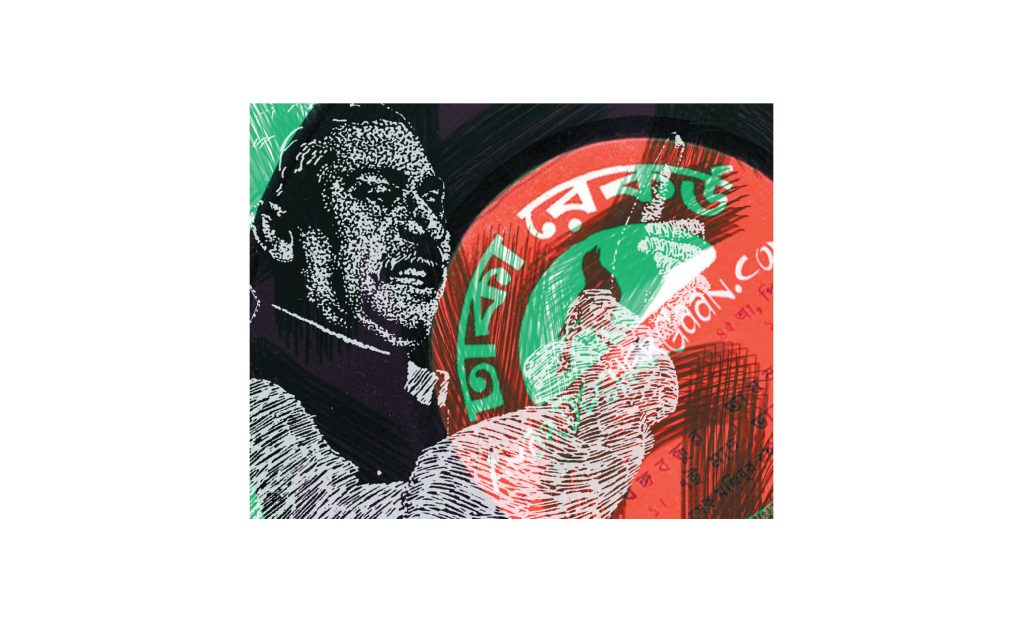

Illustration : Najib Tareque